I read “You Don’t Have to Read” by Alexandra Cage and agreed with every single word. I nodded my way through the whole thing—line by line, claim by claim, irony by irony—grateful for the clarity and relief of it. It’s a deft dismantling of the sanctimony around books, the class markers coded into the act of reading, and the petty moralism of the literary elite. It’s all true. And it’s beautifully written, too.

I didn’t read it in a book. I read it on my phone, lying on my side, screen tilted to avoid the glare of the bedside lamp. In a way, that felt like part of the point. As Cage rightly insists, the act of reading—serious, imaginative, interpretive reading—happens in more places than we’ve allowed ourselves to admit. Twitter threads, annotation chains, subtitled rants, fanfiction manifestos, niche Substacks about public transit—yes, it all counts. Reading is alive and well, just inconveniently located outside the publishing industry. The idea that we are becoming a post-literate society is lazy. What we’re becoming is a post-book culture.

And yet, even as I finished the piece and felt its arguments settle into that pleasant afterglow of confirmation, I had the odd sense that something was missing, not from the essay, but from me. From the space I’d once reserved for what books used to do. Not the idea of books, the cultural performance of reading, the tote bag with the quote from Kafka about the axe and the frozen sea—no. I mean books themselves. The object, the format, the practice.

What if books do something other forms of reading simply can’t? Or at least don’t, not yet?

I don’t have a sweeping counter-argument. I’m not here to reassert the authority of the novel or defend the Western canon. I have no interest in policing what counts as “real” reading. And like Cage, I’m tired of the performance of literary virtue, the smugness of the well-read, the cheap shot that equates intelligence with book ownership. But I’ve also read enough cognitive psychology, educational theory, and anthropology to wonder: Is there something distinct—biologically, developmentally, even evolutionarily—about reading books? Not just any books, but longform ones. Physical ones. Ones that require sitting still.

Maryanne Wolf, the neuroscientist and author of Reader, Come Home, has spent years studying how different reading modes shape the brain. She argues that deep reading—slow, sustained, linear engagement with complex texts—activates certain neural pathways that skim reading doesn’t. And guess what? Screens are optimized for skimming. The hyperlinks, the notifications, the visual layout: they train our brains to jump. Reading on screens conditions us to scroll, swipe, and abandon. It’s not morally bad. But it is cognitively different. Wolf doesn’t say we should go back to clay tablets. But she does suggest that we might be losing a specific kind of attention, and with it, a specific kind of thought.

Anthropologist Michelle Boulous Walker takes it further. In Slow Philosophy, she describes reading as an act of philosophical patience, something that cultivates the very conditions for uncertainty, ambiguity, and reflection. Books, especially difficult ones, demand that you linger. They ask you to stay with ideas longer than you want to. They’re not optimized for dopamine hits. They rarely reward you immediately. But maybe that’s the point.

I think about this a lot when I teach. I’ve seen students who are brilliant on Reddit struggle to finish a twenty-page article. I’ve seen meme fluency coexist with a kind of cognitive vertigo when asked to hold a single argument across chapters. Again, it’s not about intelligence. It’s about endurance. And books, at their best, train a kind of mental endurance that few other forms still do.

Cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham has written extensively about reading comprehension and the peculiar value of narratives. Story-based formats, especially in print, allow for what he calls “mental time travel”: the ability to simulate alternative realities, perspectives, and causal chains. This isn’t just literary romance; it’s evolutionary strategy. Homo sapiens are storytelling animals. Fiction let us model other minds. And printed novels, in particular, have historically given us the slowest, weirdest, most intricate models. There’s no autoplay. No comment section. No skip intro. Just you and the architecture of someone else’s world, page after page after page.

So yes, I agree with Cage: you don’t have to read. Not to be smart. Not to be good. Not to prove anything to anyone. But I also think there’s something about the longform book—a novel, a philosophical essay, a dense ethnography—that no other medium has quite replicated yet. At least not at scale.

You could argue that the novel is a culturally contingent format. That it rose with the printing press and will die with the attention economy. Maybe that’s fine. Maybe we’ll develop new formats that offer comparable depth and abstraction, ones that don’t require paper or patience or perfect silence. But for now, the book remains a kind of cognitive gymnasium, a place to stretch muscles that digital culture lets atrophy.

I don’t think that’s elitist to say. Or at least, it doesn’t have to be. What would it look like to hold this view without using it to shame people? To say: books do something singular—not superior, but singular—and we might want to protect that function, not because it makes us better people, but because it keeps certain neural and philosophical possibilities open. The point isn’t to worship the book. It’s to recognize that it may still be one of our most powerful technologies for cultivating thought.

And here’s the truth: I don’t know. I don’t know if books are necessary. I don’t know if we’ll find a digital substitute that replicates what they do. I don’t know if longform attention is something we’ll teach ourselves back into, or if we’re witnessing the slow decline of a very specific cognitive regime.

But maybe that’s what books teach best: how to stay in the not-knowing. How to live with complexity. How to admit uncertainty without defaulting to irony or retreating into hot takes. The best books don’t give us answers; they give us more ways to ask better questions. And maybe, if that’s all they ever did, it would still be enough.

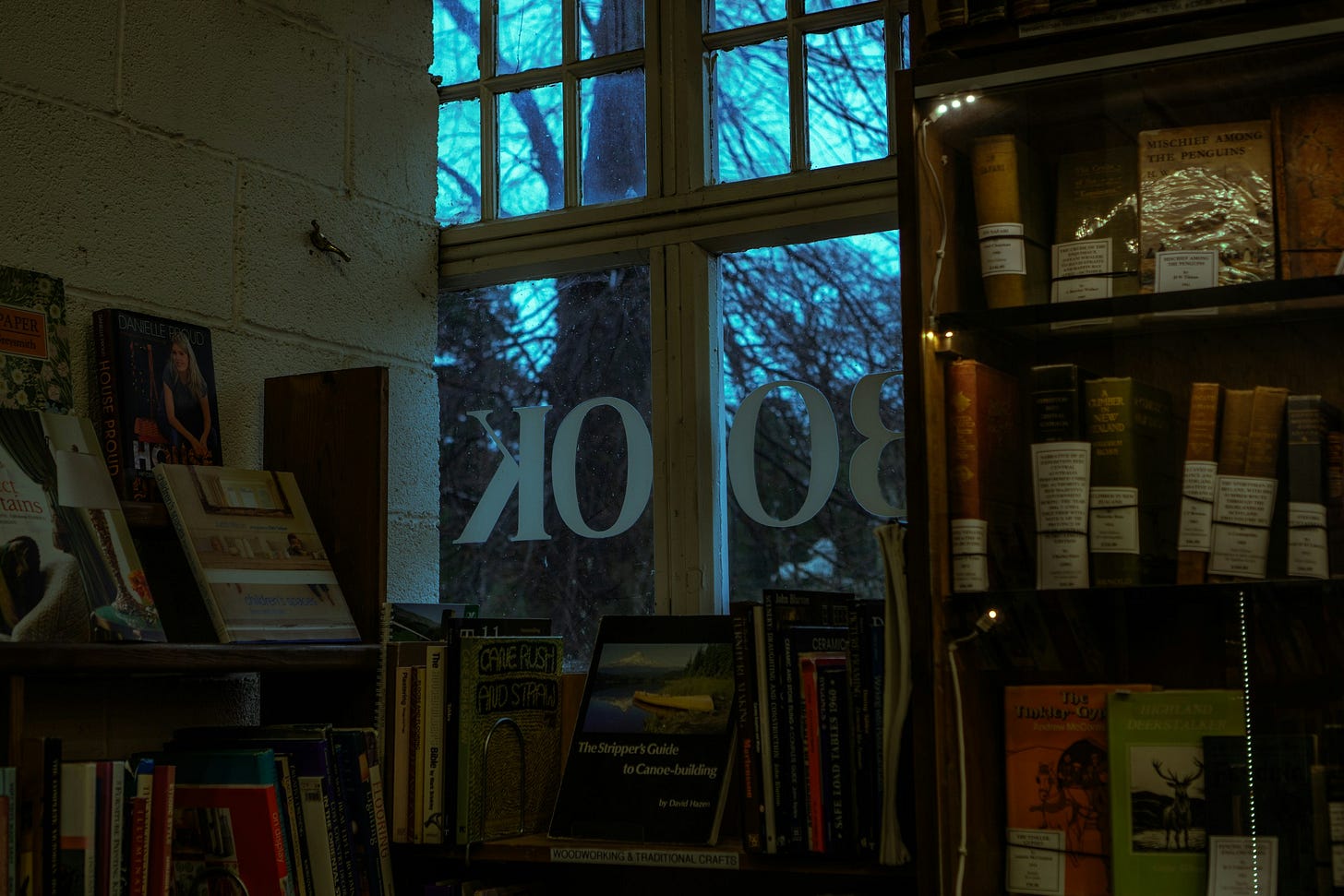

The photo was taken at Barter Books, in Alnwick, UK—the place with the castle. No particular reason. I just like the light coming through the window. Or maybe not. Just because.