Cassettes were never supposed to come back. Unlike vinyl records, which always retained an aura of audiophile respectability, cassettes were disposable, cheap, the thing you left in your car until the sun warped it. If vinyl was the format of connoisseurs, cassettes were for teenagers recording the Top 40 off the radio, stopping the tape before the DJ’s voice cut in. They were for bootlegs, love letters, road trips, and garage bands handing out demos. They were never prestigious. And yet, here we are, in an era where people buy cassettes again—not because they’re the best way to listen to music, but because they mean something.

I was born in the mid-1980s. That means I straddled the transition from analog to digital. I had cassette tapes, but I also had CDs. Then Napster came, then iPods, then streaming, and suddenly music was weightless. No rewinding, no flipping, no delicate plastic reels. Just a list of songs, infinitely available, infinitely forgettable. That’s the context for the so-called cassette revival: a reaction against music’s dematerialization, a refusal to let everything dissolve into the cloud.

But cassettes are not coming back like vinyl did. Vinyl has a clear advantage: it sounds good. It has depth, warmth, dynamic range. It’s a fetish object for people who care about sound. Cassettes, in contrast, sound bad. There’s tape hiss, there’s degradation, there’s the way cheap decks misalign and make everything slightly off-pitch. It’s not a high-fidelity medium. It’s a medium of imperfection, of small failures, of pressing play and waiting to see if the tape unspools into a mess of tangled plastic spaghetti. It’s a format of inconvenience.

So why do people buy them? The answer isn’t sound quality—it’s intimacy. Cassettes were the last physical format where you could make something yourself. You could record a mixtape, choose songs for someone, and put them in a deliberate order. You could dub a bootleg, copy an album, make something material. In the 1990s, people passed around Nirvana bootlegs and punk demos. In the 1980s, hip-hop DJs in the Bronx sold live recordings straight from their sets. In the 1970s, activists used tapes to distribute banned speeches. Cassettes were never about fidelity—they were about access, about presence, about making music move.

Today, that function has largely disappeared. Playlists are the new mixtapes, and they’re infinitely shareable, but they don’t have weight. You don’t need to ration space when you can add an unlimited number of songs. You don’t need to think about sequencing when you can shuffle. You don’t need to rewind when everything is on demand. Convenience wins, and cassettes lose—except when they don’t.

Look at indie bands today. Look at underground labels. They’re selling cassettes, not because they sound good, but because they’re cheap. Pressing vinyl is expensive; CDs feel obsolete. A cassette costs a few dollars to make, and that means an artist can sell something real at a merch table for the price of a beer. They know most people won’t play them—half the buyers don’t even own a tape deck—but that’s not the point. The point is that someone holds it in their hands. The point is that it’s a thing.

And yet, let’s not romanticize. Nostalgia has a way of erasing the frustration of a medium. Cassettes were never easy. Tapes wore out. They snapped. If you had a Walkman, you had to carry extra batteries because the damn thing drained them in an hour. Car tape decks ate tapes. If you wanted to hear a song again, you had to hold down rewind, guess when to stop, and then probably overshoot. It was effort. Music required effort. That’s the nostalgia—not for the sound, but for the act of listening as something that took time, that had stakes, that wasn’t just background noise.

But nostalgia alone doesn’t explain why cassettes still exist. They persist in niche markets, in experimental music, in DIY scenes. In places where what matters is not just the sound, but the object, the process, the act of making something. That’s where cassettes live. Not because they’re better. Not because they’re easier. But because they’re something—and in a world where music is increasingly nothing, that still counts.

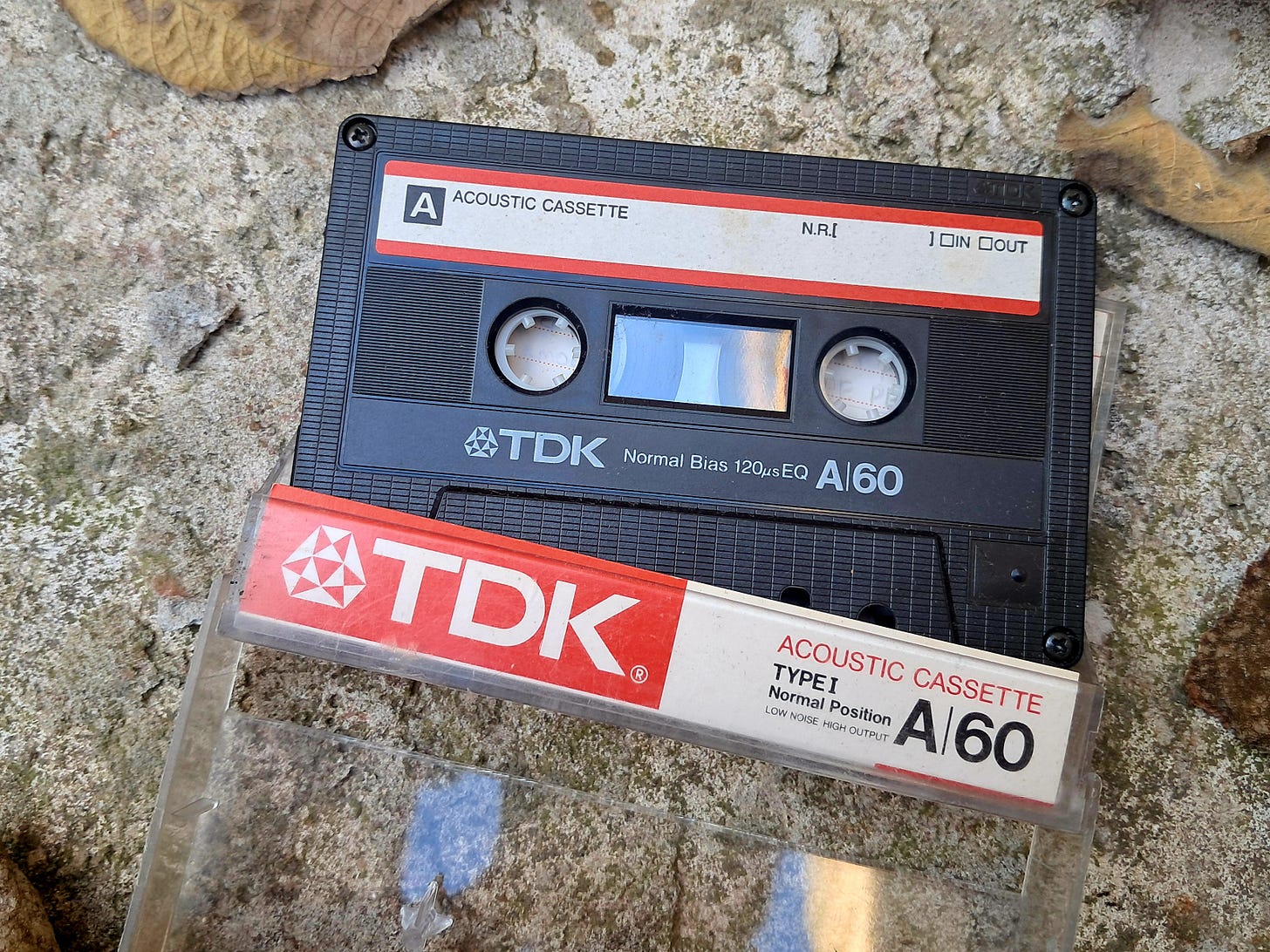

I took this photograph on Bedford Avenue, just above the tracks, at the entrance to Brooklyn College. What mysteries did it hold? I left it where it was—because I don’t have a cassette player and because I’ve seen too many horror movies.